Let me guess: when you decided to write a family history book, you imagined yourself as a kind of genealogy Indiana Jones — dodging cobwebs in the attic, uncovering ancient love letters, maybe discovering your great-great-grandmother was a secret suffragette spy.

Instead, you found… three names on a census, a photocopy of someone’s elbow, and a confusing family story involving “a cousin who ran off with a circus goat.”

Don’t worry — you’re not alone!

Writing family history often means trying to build a puzzle with half the pieces missing, and no picture on the box.

But here’s the thing: you don’t need perfect records to tell a powerful story. You just need a little creativity, some historical duct tape, and a sense of humor.

Whether your great-grandpa left behind a detailed journal or just a really solid mustache in a 1901 photo, you can write something meaningful.

Here are 15 tips to help you turn even the sparsest facts into a story your family will love — and maybe even pass down for generations (circus goat and all).

1. Start with What You’ve Got (Even if It’s Just a Grocery List and a Gut Feeling)

You don’t need to start with a treasure chest — just a breadcrumb or two.

A name, a town, a suspiciously vague birth year like “around 1890-ish.” That’s your starting point.

Even if all you know is that your great-uncle Frank “was tall and once punched a cow,” you’re in business.

Start organizing what little you do have, no matter how small or weird. Use timelines, charts, sticky notes, spreadsheets — whatever keeps your brain from melting.

The trick is to treat each fact like a hook you can hang something on later.

2. Use History Like a Time Machine

You might not know what your ancestors had for breakfast — but if they lived in Chicago in 1871, odds are, breakfast came with a side of smoke and chaos, courtesy of the Great Chicago Fire.

Dig into the events, trends, and daily life of the time and place they lived.

- What did people wear?

- What did they eat and drink?

- What was in the news?

- Were there wars, plagues, or fads involving raccoon coats?

This isn’t fluff — it’s context, and it helps your reader (and you) picture their world.

Historical context turns “a woman named Martha in 1920” into “a woman named Martha who probably voted for the first time, wore bobbed hair, and dodged prohibition agents while sipping bootleg gin.”

3. Dig Into Culture and Careers

If you discover that your ancestor was an Irish fisherman, a British midwife, or a Swedish carpenter, congratulations — you’ve just unlocked a treasure trove of story material.

What was that job like back then? What kind of tools did they use?

What cultural beliefs or traditions shaped their lives?

You can paint a vivid picture without ever seeing their face just by learning about the world in which they worked and lived.

(And yes, that may mean figuring out what a caudle is and why they fed it to women in labor)

4. Tell a Story, Not Just a Timeline

“Born. Married. Moved. Died.” is technically a family history, sure. But you’re not writing a tax return — you’re telling a story.

Give your reader something to feel.

Were your ancestors heartbroken when they left their homeland? Did they open a bakery during the Great Depression and keep everyone fed with ten-cent pie?

Add emotion. Add texture. Add the smell of warm biscuits and the sound of a squeaky screen door.

And when you need to fill in blanks, be honest about it:

“While we don’t know exactly how Emma felt leaving Ireland, it’s likely she shared the mix of fear and hope many immigrants carried as they stepped onto the boat that would change their lives.”

See? Beautiful, accurate, and totally responsible.

5. Gently Shake the Family Tree and Talk to Living Relatives

Don’t underestimate the power of calling your Aunt Betty. Even if she’s 87% tangents and 13% facts, she might remember the nickname your grandfather hated, or the strange tattoo your great-uncle had of a toad.

Those little details are storytelling gold.

Memory is fallible, yes — but it’s also full of texture, emotion, and insight that documents don’t always provide.

Bonus: You’ll probably hear a few juicy secrets along the way. Just remember, with great family tea comes great responsibility.

6. Channel Your Inner Novelist with the Five Senses

Even if you don’t have exact details, you can imagine what things looked, sounded, and smelled like in a given time and place.

- What did a 1920s kitchen in rural Arkansas smell like? Probably a mix of wood smoke, lard, and cornbread.

- What did a family farm in 1880s Ireland feel like? Most likely it was rugged and earthy, with wind sweeping across stone-fenced fields, the rhythmic creak of a wooden cart, and the mingled aromas of damp soil and turf fire.

Add those elements to your story.

Sensory details make your story feel alive. You’re not lying — you’re bringing history to life using everything we know about the era. (And maybe adding a few roasted chickens for flavor.)

7. Celebrate Unique Family Traditions

If your family always buried a slice of cake in the backyard for good luck or used pickle juice as a cold remedy, write it down.

These rituals, however odd, give your story personality. They show continuity, culture, and just the right amount of family weirdness.

Remember: no one ever said, “Wow, I loved that family history where nothing unusual ever happened.”

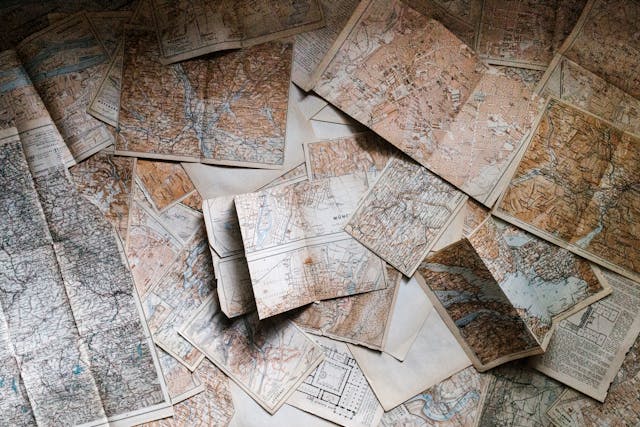

8. Throw in a Visual or Two

Even if you don’t have personal photos, include things like:

- Maps of the towns where your ancestors lived

- Photos of typical clothing, houses, or workplaces from their era

- Snippets of census records or ship manifests

Even a photo of a steamboat like the one your ancestor might have taken can anchor your reader in time and space. A little visual flair goes a long way toward making history feel real.

9. Be Upfront About the Gaps

You don’t have to pretend you know it all. In fact, it’s better if you don’t.

Readers will appreciate your honesty — and your humility.

Instead of faking confidence, try something like:

“The records are sparce on what happened during these years, but based on the region and the time, here’s one possibility…”

This builds trust and makes your reader part of the mystery. Plus, it leaves room for someone else in the family to come along later and add to the story.

10. Use a Sibling, Neighbor, or Random Guy Named Earl

Let’s say your ancestor, Harriet, didn’t leave behind a single scrap. But her sister Clara married a dentist in the same town and left behind 40 pages of journals. Jackpot!

You can glean a ton from those nearby lives:

- Who were the people who lived next door?

- What other families attended the same church?

- Who were some of the men who served in the same Army unit?

It’s like triangulating history with people who were breathing the same air.

(And if one of them was named Earl, all the better.)

11. Pick a Theme and Run With It

Don’t just write what happened — write what it meant.

What’s the thread tying everything together?

Maybe it’s resilience, migration, faith, reinvention, or just the uncanny ability to lose everything at poker and still come out on top.

A theme helps guide your storytelling choices and gives the book emotional depth.

Think of it like a family history Netflix series: there’s a main plot, but also a deeper message. Lean into that.

12. Notice the Patterns (and the Oddities)

Sometimes family history reads like a weird game of Bingo:

- All the men are named John? Check.

- Everyone marries someone named Mildred? Check.

- Three generations become undertakers for no reason? Strange — but check.

Patterns are fascinating!

Repeated names, migration routes, or career paths can hint at values, personality, or just plain stubbornness. They’re clues, and they make great talking points in your writing.

13. Yes, You’re Allowed to Talk About Yourself

You’re the one doing the digging. You’re the narrator.

If you want to include the time you cried over an 1890 census page or the thrill (or disappointment) of discovering your ancestor wasn’t a bootlegger — just a terrible speller — that’s part of the story.

Your curiosity is the heartbeat of the book. Don’t be afraid to let your voice come through.

14. Make the Past Feel Like the Present

Connect the past to the present.

- Maybe your ancestor sewed her own clothes to save money, and now your cousin has an Etsy shop doing the same thing.

- Maybe your great-grandfather ran a barbershop, and your nephew just opened one last week.

These echoes across time add a layer of warmth — and help your readers see that history isn’t some dusty thing in the attic. It’s them.

15. Embrace the Chaos and Write Anyway.

You’re not going to have all the answers. And that’s okay.

This book doesn’t have to be perfect — it just has to be honest. Real. And told with love.

Whether it’s 300 pages or 30, whether you’ve got a full family archive or just a few curious clues, what matters is that you’re preserving a story worth remembering.

And hey — maybe one day, someone in the next generation will pick up where you left off and fill in the gaps with newly uncovered information.

Final Thoughts: The Circus Goat Was Just the Beginning

Writing family history without all the records might feel like trying to assemble IKEA furniture without instructions… and with three missing screws. But it can be done — and done well — with heart, humor, and a little creative elbow grease.

So tell the story. Stitch together the scraps. Own the chaos.

And if you ever need a hand wrangling census records, decoding old handwriting, or just figuring out how to make Great-Aunt Doris seem less terrifying on paper — we’re here to help.

Reach out anytime. We’ve got storytelling glue, genealogy goggles, and plenty of coffee.

| Need help writing your book? Contact us today to learn more about our ghostwriting services. Let us help bring you story to life. |