Every family has a few objects that seem to hum with the weight of the past. Objects of power — like a watch that never kept perfect time but somehow outlived three owners, a recipe card smudged with flour and four generations of fingerprints, or a brooch tucked into a drawer for decades, its story half-told every time someone lifts the lid and says, this belonged to your grandmother.

These things outlast the people who held them. For writers, they’re narrative keys.

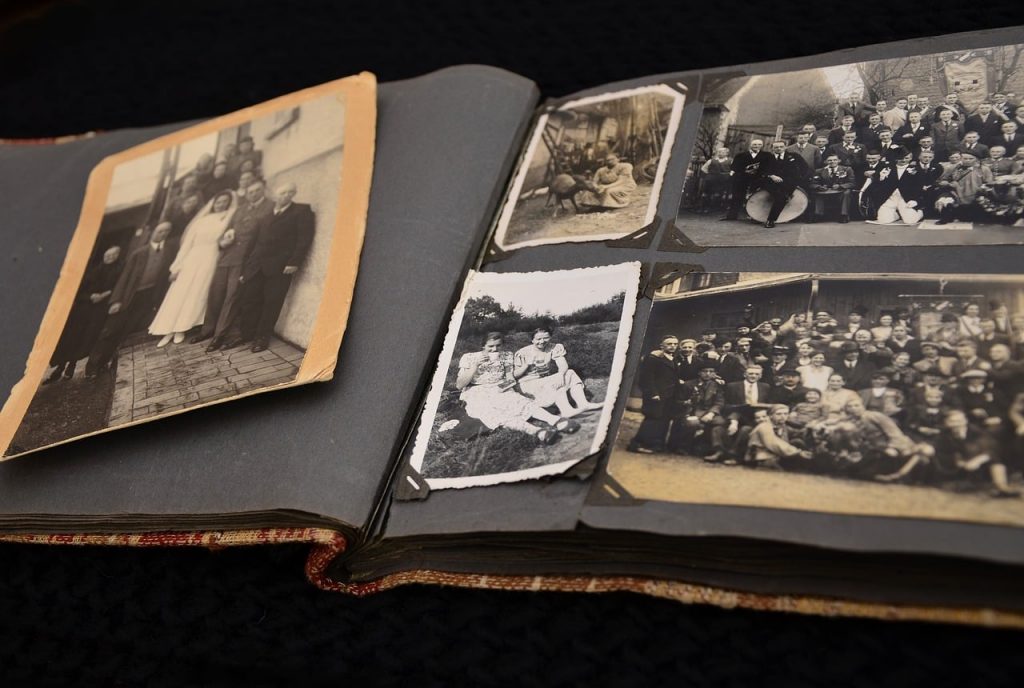

Objects give memory a physical shape by letting you touch the intangible. Family historians often start with photographs and records, but heirlooms reach deeper — past what’s documented into what was lived.

“She gathered the ragged pieces of her memory and came up with a quilt. No one could tell her that the pieces were not real.”

— Toni Morrison, Beloved

The best family histories do just that — stitching memory to matter and imagination to evidence until the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Heirlooms remind us that family history is a dialogue between generations. They let the past interrupt the present, insist on being remembered, and demand to be written.

The Story Objects Tell

Every object that survives the churn of time has done so because someone, at some moment, decided it mattered. That act of keeping is the first gesture of storytelling. It says, this object stands for something.

Anthropologists and psychologists alike have noted how heirlooms act as vessels of continuity, binding the private self to the wider family narrative.

Karen Lillios, in her research on heirlooms and archaeology, described them as “objects of memory” — material carriers of identity that signal the passage of meaning across generations.

The archaeology may be ancient, but the principle is timeless. A child who keeps a grandparent’s pen or medal performs the same act of preservation as someone who buried a relic thousands of years ago.

Writers who approach these objects learn that meaning shifts as they move through time. A wedding ring might first represent commitment, then endurance, then loss, and eventually hope. The item doesn’t change — the interpretation does.

“Real museums are places where Time is transformed into Space.”

— Orhan Pamuk

Objects also hold contradictions. They can bring comfort or unease, connection or distance.

A locket might carry a hidden photograph no one recognizes, raising questions about love or secrecy. A military medal can evoke both pride and pain.

When a writer includes these tensions, the object becomes multidimensional — a story in itself rather than a prop.

Choosing the Right Objects to Tell the Story

Every home — even the smallest apartment — contains more history than its occupants can hold in their hands. Drawers fill with relics that seem to multiply: photographs with no names, half-repaired jewelry, chipped china, and old ticket stubs that once meant something.

When you start writing a family history through objects, the first impulse is to include everything. Yet the strength of this method lies in curation.

The right heirloom is the one that refuses to let go of you. You might find yourself returning to it, turning it over, wondering why it matters when you can’t quite explain. That’s your signal.

Ask yourself:

- What broader theme does it whisper?

- What does this object remember that people have forgotten?

- Who last touched it, and what did that moment mean?

Answer those, and you’ll know whether the item can carry narrative weight.

Fragile items like letters, textiles, or paper often reveal private emotion. Durable ones — tools, furniture, jewelry — speak of work, endurance, and lineage. Together, they demonstrate what a family valued and what it endured.

A metal key might represent ownership and safety. A cracked teapot might suggest gathering, nourishment, or grief. Each opens a different door into memory.

“Every patch of fabric matters, yet the power of the quilt lies in composition — the patterning that turns fragments into something whole.”

Structuring a Family History Around Objects

Once the objects are chosen, the real craft begins: deciding how to let them tell their stories. A family history written through heirlooms should feel less like a guided tour through a museum and more like walking through a lived-in home — each object its own room.

1. The Chronology of Ownership

Track the passage of an object through hands and time. A gold wedding ring, for instance, can move through generations, accumulating layers of meaning — love, sacrifice, endurance, even betrayal. The rhythm of inheritance becomes the story’s backbone.

2. Thematic Clustering

Group objects by the emotional or cultural work they perform. You might devote one section to migration — passports, ship tickets, suitcases — and another to domestic rituals: cookware, linens, or tools of craft. Repetition of theme builds cohesion and shows how values evolve across eras.

3. The Spatial Approach

Organize by room or setting: the kitchen, attic, or garden shed. Each space holds a different register of memory and invites readers to inhabit the story as though exploring the ancestral home itself.

Whichever structure you choose, begin with the tangible. Describe before interpreting. Let readers see the scratches, smell the cedar, and feel the dust in the folds.

“The present rearranges the past.”

— Rebecca Solnit

A story told through objects allows for recursion, echo, and layering — just as memory itself does.

Good pacing matters too. A reader needs space to pause between artifacts, the same way a museum visitor needs time between exhibits. Short interludes, photos, or letter excerpts can serve as breaths between heavier sections.

And one of the most effective tools? Echoing detail. A recurring phrase, color, or motif — like a blue thread in a grandmother’s quilt reappearing in a granddaughter’s dress — builds continuity across time, creating invisible filaments of heritage.

Inheritance, Memory, and Meaning

Objects outlast us. They remember in ways we cannot, holding our gestures, our wear, our weight. Writing a family’s story through its heirlooms is an act of translation — turning the silent language of things into sentences that breathe.

“People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.”

— James Baldwin

The chipped plate that crossed an ocean, the military medal hidden in a drawer, the diary sealed in a tin box — each is both a relic and a mirror. Through them, history stops being something that happened and becomes something still happening today.

The physical object gives memory something to cling to, while memory gives the object meaning beyond itself. In doing so, you transform inheritance into art.

The work is also forward-facing. Every story captured through an heirloom becomes part of someone else’s inheritance. Future readers — perhaps family members yet unborn — will find themselves in those sentences, recognizing gestures and rituals that feel like home.

For writers, the task isn’t simply to record what an object is, but what it means now. The moment you lift an heirloom from a shelf, you join its story to your own — ensuring it never falls silent again.

From Keepsakes to Stories

If you’re ready to transform your family’s keepsakes into stories that live beyond the attic or the archive, you don’t have to navigate that task alone.

At The Writers For Hire, we specialize in helping families shape their legacies into lasting narratives — blending research, craft, and care.

Whether you’re starting from a single heirloom or a house full of history, our team can help you capture the voices, textures, and meanings within them.

Reach out today, and let’s turn your family’s objects into the living stories they were always meant to be.