African American Lineage: 9 Steps to Tracing the Ancestry of Slaves

AFRICAN AMERICAN LINEAGE: 9 STEPS TO TRACING THE ANCESTRY OF SLAVES

For many people wishing to trace their heritage back to the time their ancestors immigrated to America, there are numerous sources and resources available.

But what if your ancestors did not come to this country of their own free will? What if, instead, they were brought here hundreds of years ago by slave traders?

Often, for people with African ancestry, it seems impossible to trace lineage beyond a handful of generations. This serves as a stark reminder that just over 150 years ago, black people were seen as property, and were treated and documented as such.

While the abhorrent practice of slavery definitely makes it difficult to trace the ancestry of people forcefully brought here from Africa, with a little digging and a keen eye, it’s not impossible. And, in most cases, the first step is finding the names of the slave owners.

But how is that done? And how does knowing the name of the slave owner help track the African American’s ancestry?

Keep reading, as we show you how with these nine helpful steps.

9 Steps to Tracing the Ancestry of Slaves

1. Start with oral history.

When it comes to any kind of genealogical research, the best place to start is with what you and your family members know.

If you don’t know anything beyond your grandparents’ generation, for example, talk to the oldest members in your family and find out what they know. Ask them for stories that were passed along to them by their grandparents.

While oral history is not always 100 percent accurate, it generally contains at least some truth. And chances are, there are clues hidden within the stories your grandparents were told.

Use those clues to figure out where your ancestors lived 100 years ago, how they made money, or the names of their parents and siblings.

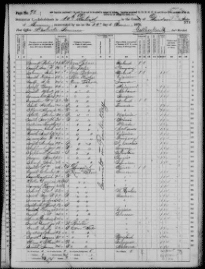

2. Use the 1870 Census records to find clues.

If you can pinpoint approximately where your family lived right after the Civil War, chances are you may be able to locate them on the 1870 Census.

This is the first census that included the names of former slaves.

That’s because prior to 1865, slavery was legal and only 10 percent of African Americans were free. And, because they were considered property, the names of slaves were not generally included on the census.

Once you have located your ancestors on the 1870 Census, take note of all of their names and ages.

These are going to be the clues you will need to locate them on earlier census records.

Next, check the census records for white families in the area with the same or similar last name. While many former slaves changed their names once they were freed, some of them kept the surnames of their former owners.

Using the names of white families in the area with the same name, you can then check the 1860 Census and slave schedule to see which of those families were slave owners.

Although slaves were not usually listed by name on those census records, they were sometimes listed by age and occasionally first name.

By subtracting 10 years from the ages of your ancestors in the 1870 Census, you can search for white households with slaves that match the names and ages of your ancestors in 1860. Then do the same for 1850, 1840, and so on.

While census records can provide a lot of key information, the biggest thing you’ll want to take note of is the name of the earliest slave owner. This will give you more clues as to how to trace your family back even further.

3. Check wills and probate records.

Once you think you’ve found the name of the earliest slave owner, you’ll want to find any wills or probate records for that person.

Sadly, as slaves were seen as possessions, they were often listed as an owner’s assets, alongside things such as livestock, farm equipment, furniture, and household goods.

And just as those things were passed along in wills, slaves were also frequently left as an inheritance to the deceased owner’s family.

Finding your ancestor listed in a slave owner’s will and probate can give you clues to other enslaved family members that may have resided in the household. It can also give you a name for the person to whom those family members were given.

Likewise, finding the will or probate for a slave owner’s father can possibly show how that slave owner came to possess the slave in the first place.

4. Search the Freedmen’s Bureau.

If finding your ancestors on the census or in wills and probate records was not a success, it’s possible they can instead be found in the Freedmen’s Bureau catalog.

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (also known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) was established in 1865 to help newly freed African Americans transition to life outside of slavery.

Although the Bureau was abolished in 1872, its catalog of resources is a very valuable asset for those looking for information on former slaves.

From 1865-1872, the Bureau tracked everything from marriage records and labor contracts to housing and sharecropping agreements.

And many of those records included the name of the former slave owners.

If you are able to find your ancestors on any of these records, chances are high that you will also find the names of their former owners. From there, you can pop back into the census records again, and track backwards to the earliest slave owner.

5. Search the Freedman’s Bank records.

The Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, also known as the Freedman’s Savings Bank, was established in 1865 as a way to help former slaves establish financial stability and independence.

The Bank’s records, which can be searched online, frequently contain information such as dates of application, account numbers, and the depositor’s name, signature, age, complexion, place of birth, place raised, occupation, spouse’s name, children’s names, and other family members’ names. Additionally, many of the records also include the name of the former slave owner.

6. Check military records.

Military records possess a wealth of knowledge if you know what you’re looking for.

More than 178,000 free blacks and freedmen served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) during the Civil War. If your ancestor was one of those men, their service records can be found in the U.S. Colored Troops Military Service Records database.

From there, you can use their information to find them in the Civil War Pension Index, which often lists the names of slave owners, as well as information about the regiment in which the soldier served.

In addition, many of the pension applications include explanations of name discrepancies.

For example, for a former slave who changed their name, the record may be under the slave owner’s surname.

So, the pension application may contain a statement saying, “When I enrolled, the military used my slave owner’s surname of Smith, but my real name is Jones.”

Again, this is a good way to find the name of the former slave owner, which can then be used to track them on the census records prior to 1870.

7. Use historical records databases.

The African American Historical Record Collection as well as the database of U.S. Interviews with Former Slaves contain thousands of first-person interviews with former slaves, slave manifests, slave emancipation records, and hundreds of black and white photographs of people who were formerly enslaved.

Both databases are easily searchable, so ancestors can be found using anything from first and last names to dates of birth, marriage dates, places lived, and more.

The stories and information housed within these collections often contain priceless clues that can help trace ancestry even further.

8. Take a DNA test.

While a DNA test is not going to give you all of the answers you’re looking for, it can at least confirm the presence of your ancestors in a particular part of the country. And for people who don’t know where to search, this can give you a place to start.

In addition, DNA tests can match you up with people with shared ancestors. By reaching out to those people and finding out what they know, you can frequently find more pieces to the big puzzle that you’re trying to solve.

Unfortunately, though, when it comes to finding out where your ancestors came from before they were brought to this country as slaves, most DNA tests fall short.

This is because most of the major DNA companies, such as Ancestry and 23andMe, have limited representation for people outside of European heritage.

So, results for people of African ancestry are not very informative or detailed.

That being said, by adding your DNA to these databases, you are helping to expand representation for people of your heritage, which will eventually result in more accurate and precise results.

In fact, 23andMe now has a program dedicated to diversifying their database and increasing representation from underrepresented populations around the world. Their program, called the Global Genetics Project, offers people free test results in exchange for their saliva donation, if all four of their grandparents were born in an under-sampled region of the world.

9. Hire a professional genealogist.

Sadly, tracing African American ancestry is no easy task. It takes a lot of time, patience, and a ton of extensive research.

If you have tried researching your ancestry, and find that you keep hitting dead ends, consider hiring a professional genealogist.

A professional genealogist will have the tools and experience needed to get past all of the brick walls and red tape to locate your ancestors and give you the answers you’re searching for.

Related Content

- 0 Comment

Subscribe to Newsletter

- Elevate Your Content: How To Use Canva for Eye-Catching Visuals

- These Tools Are Your Key to the Content Campaign Kingdom

- Strategic Content Marketing: Distribution Methods for Maximum Reach

- The Abilities and Limitations of AI in Content Creation

- How to Use AI to Power Up Your Marketing Communication Strategy