Can you secure a book deal before you even finish writing the book? Sounds too good to be true, but if the book is nonfiction, it’s in the realm of possibility. It all starts with a book proposal.

As an expert, you know your subject and have plenty to say. Writing a nonfiction book is the way to do it, but you may wonder how to turn your ideas into a book on the shelf. Maybe you are an expert on the changing landscape of world politics? Or, a seasoned self-help professional with a thriving YouTube channel? Perhaps your life story and family history are guaranteed to capture the interest of readers the world over.

Like many nonfiction writers, you are knowledgeable in the subject matter, but your expertise probably doesn’t cross over into book-proposal writing. Fortunately, pitching a nonfiction book follows a fairly predictable path.

Pitching novels and other works of fiction is an entirely different endeavor than pitching nonfiction. When you are working with fiction, excellent writing is the key. Pitching fiction usually involves a query letter, synopsis and manuscript, and your goal is to wow the publisher with a story that has never been told.

But, if you pitch a biography, memoir or how-to nonfiction book with the same approach as you would a novel, your pitch will likely end up in the trashcan (or, perhaps more realistically, the delete box).

- What is a Book Proposal?

In the simplest of terms, a book proposal is a document you submit to an agent or a publisher to sell your nonfiction book. It’s not just a description of the book, but rather it is a sales pitch. It demonstrates to the publisher how they can easily sell and make money from your book.

When putting together a nonfiction book proposal, think like a publisher and not like a writer.

The proposal has to be well written, with a hook that sets it apart from others. If you are not an experienced writer, it may be worth your time and expense to use a consultant or ghostwriter to craft your proposal.

Creating the document is not a one-size-fits-all process, and there are all sorts of variations. But, the best proposals all contain the essential details publishers need to make a decision on whether or not to seek more information on your book. Here is the information you should include:

1. Overview

2. Chapter Outline/Sample Chapter

3. Competitive Analysis

4. Target Market

5. Author Bio

6. Marketing/Sales Plan - Pitching Nonfiction is (Very) Different from Pitching Fiction

Catching a publisher’s attention with a nonfiction book is very different from selling a novel. In fact, the processes have little in common. Jennie Nash, founder and chief creative officer at Author Accelerator, says it’s not enough to pitch what the book is and who it’s for. “Nonfiction pitches have to include a marketing plan and platform. You have to show how you are going to reach your audience,” Nash said.

The first step is to learn what publishers want. Unlike fiction, publishers may not ask to see a completed nonfiction book. But, they will definitely want a unique book proposal that demonstrates how YOU can market the book to the target audience.

The most critical component of a nonfiction book proposal isn’t the subject matte or your technical writing ability. Publishers want to see a solid marketing plan. - Pitching an Agent vs. Pitching a Publisher

One of the first decisions you must make is whether or not to use a literary agent. Going directly to a publisher is always an option, but many writers (especially new, unpublished writers) choose to work with an agent. By hiring one, you are buying access to their working relationships with publishers.

If you are not already an influencer in your industry, you may be facing an uphill climb. Working with an agent gives you an “in.” Not only is a good agent a credible champion for your pitch, but they know the right people and have an idea of which publishers are more likely to be receptive to your specific book.

An agent is your advocate in the publishing world.

They usually work on commission, so it’s in their best interest to find you the best book deal. Their job is to position your book to sell. But they don’t do everything.

Agents:- Do not edit your book

- Do not buy it from you, first, and then approach publishers

- Do not guarantee publishing success

It may not be necessary to use an agent if you have already been published, or if you are well known in your industry. In those cases, you can save some money by skipping the agent.

If you pitch directly to a publisher, be sure to follow their specific proposal instructions. Each publishing house does things a little differently, and it is essential that you give them the information in the format they prefer. Countless proposals cross their desks, and if yours doesn’t follow their rules, you can bet it won’t make the cut.

Can’t decide? Think about your ability to catch a publisher’s attention on your own. If you are new to book writing or just starting to establish yourself as an industry expert, an agent may be a good idea. Whether you work with an agent or forge your own path, the elements of a book proposal are the same. You are still selling your book and marketing plan; the only difference is whether your buyer is an agent or publisher. - How to Find a Literary Agent

A good place to begin your search for an agent is with some online research. Check out these agent-search websites:

Publisher’s Marketplace

Agent Query

Query Tracker

Many writers say Publisher’s Marketplace is a great resource. It requires a $25 per month paid subscription, but may be worthwhile for a short time to gain access to their database. The site allows you to search agents by genre, and also shows current book deals so you can get an idea of how your category is represented.

You can also take a look at other books in your niche or genre. Who agents those authors? Sometimes identifying an author’s agent is as easy as reading the acknowledgement section of their books. If an agent has represented a book in your category, they may at least be open to reading your proposal. Once you identify some possibilities, search for their social media profiles. Many agents post when they are actively seeking new authors and submissions.

6 Steps to a Winning Nonfiction Book Proposal

Remember: if the proposal isn’t effective, the book won’t be published.

Step 1: Overview

This is the opportunity to immediately catch the publisher’s attention. Think of the overview as an enticing description that makes you want to read more. Basically, it’s the blurb you would find on the book jacket cover.

Start off with a short introduction that sums up the book in just a few sentences. If you only had one minute to tell someone what your book is about, what would you say? Next, get into a deeper description about the book to let the publisher know what to expect from the rest of the proposal.

Proposal overview essentials: What is it about? Who will read it? Why will readers care?

Nonfiction writer Bryan Collins wrote a great blog post for his blog, Become a Writer Today, about how to put together a proposal overview. Check out this real example of a strong proposal for a memoir:

Step 2: Chapter Outline/Sample Chapter

The best way to explain what’s in your book is to show the list of chapters. Include a complete list of the chapters, with a short description for each. Don’t get carried away with overly detailed, lengthy explanations for each chapter. Keep it short, but be sure to clearly define the scope of the chapter and show how it fits into the book.

A sample chapter lets you show the publisher exactly how the book will read. You have told her what will be included in the book; now, show what that means with a complete, polished chapter. Choose the very best chapter you have. It should personify the promises you made in the overview, and leave the publisher wanting to know more.

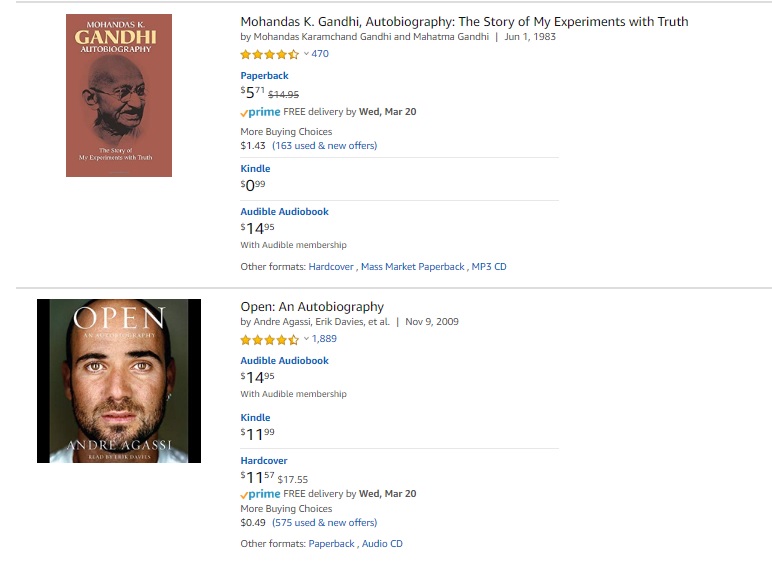

Step 3: Competitive Analysis

Is there space in the market for your book? That’s the question publishers need to answer when they read your competitive analysis. Your job in this section is to show several (approximately 5-10) current books that belong to the same category as yours. Imagine your book on the shelf at the local book store, and tell the publisher what other books would be next to yours.

Not every book in your category is a true competitor.

Be realistic. Consider the fact that in addition to being an industry expert, a bestselling author may have a significant platform that converts to sales. If you are a first timer with limited platform or industry influence, then a wildly successful bestseller probably isn’t your competition.

A good way to search for competitive titles is to visit a bookstore. Decide where you think your book fits on the shelf, and then go to that shelf at the bookstore. It’s not necessary to read each of the books, but do some research. Find a synopsis and the table of contents, and read reviews.

Amazon and Google are other places to identify the competition. A quick search of the category will bring you to plenty of titles to research.

For each competitive title, include the following information:

- Complete Title

- Author’s Name

- Publisher’s Name

- Date of Publication

- Page Count

- Price Point

Simply listing titles and authors isn’t enough. For each one, explain how your book takes a new or different approach to the subject. If your book includes new research not found in other books, say so. If your book challenges a commonly held belief found in other books, say so.

This is the time to humble-brag about your book. Don’t be afraid to articulate why your book is better, but don’t harshly criticize other authors. Simply point out how your book fits on the shelf as the newest, latest and best read on the topic.

Step 4: Target Market

Identifying a specific, quantifiable target market is a must. Publishers expect you to not only define that audience but also to quantify it. A well-written book about a subject very few people care about won’t sell enough to justify publishing.

Nash points out that nonfiction has a smaller target market than fiction:

“The fiction market can never have enough romance novels,” she said. “But if you are writing a nonfiction book, it’s easier to target much more specifically.”

Let’s say you are writing that book about the changing landscape of world politics. Who is your target audience? Well, unfortunately it’s not as broad as the world population or even as broad as all of the registered voters.

You can begin to narrow down your potential audience by looking at the specific political cultures your book discusses, then identifying the number of people who are politically active within those cultures. Facebook pages, political organizations, and community events give clues to the number of people who are truly in your target audience.

In addition to quantifying your audience, you need to describe it, demographically. Who among those quantified politically active people will read your book? Is it gender specific? How old are these people? Where do they live? What is their income level?

Step 5: Author Bio

This is the part where you sell yourself. Tell the publisher why your experiences and expertise uniquely position you as the best person to write the book. Demonstrate your reach in the industry with examples of previous publications, speaking engagements, online presence, and media coverage.

If you have never been published, you might not have any of those, and that’s ok. It makes it more difficult, but not impossible. Keep reading, and in Step 6: Marketing Plan, we will discuss ways to create or expand your author platform.

Step 6: Marketing/Sales Plan

This is the most important part of the entire proposal. Repeat: the most important part.

Now is the time to demonstrate how you can market the book all by yourself. Publishers want authors who come with a target audience ready to buy their book. Avoid discussing things that are only ideas. This is the place for tangible steps that you are currently taking, or can realistically expect to take when the book is published.

Here are some examples of specific marketing tactics you might implement:

- Distribute information about the book launch via an email newsletter from your blog with 5,000 subscribed industry readers.

- Upload a video, showing you discussing the new book on your YouTube channel that reaches 10,000 industry subscribers.

- Promote the book at an upcoming convention of 1,000 participants, where you are a scheduled speaker.

At this point, if you don’t have substantial industry reach you are probably starting to panic. Don’t. Many writers have published successful books without being a household name in the industry.

So, how do you market your book if you have no author platform?

Platform (noun): an ability to sell books because of who you are or who you can reach

If your platform is nonexistent, you may need to take a step back and work on that before submitting a proposal. “There are a lot of people who are experts in what they do, but they don’t have an industry presence. That makes it very tricky. You have to prove you can attract the readership,” said Jennie Nash.

Many nonfiction writers have started from scratch and quickly built up enough of a platform to create a compelling author bio and marketing plan. The most obvious place to start is online:

- Create an Instagram or Facebook page that positions you as an expert and provide consistent, updated information.

- Approach established bloggers about guest blogging on their site.

- Write opinion pieces and pitch to online publications. Having a byline gives you credibility.

Industry influence doesn’t always have to be online. Consider public speaking to targeted industry groups. Where can you get on the agenda and share your expertise with an interested audience?

“You need some proof that you know how to connect with the readers, because the publisher is taking a big bet on you.” – Jennie Nash

Should You Self-Publish Instead?

If building a marketing platform and selling your socks off to agents and publishers doesn’t sound like fun, don’t panic. You don’t have to give up your dream of publishing your book.

These days, many writers are opting out of traditional publishing, and skipping the book proposal process entirely. The decision to self-publish gives writers more autonomy over their material and distribution plan. But, it requires the writer to coordinate the entire process, which can be overwhelming.

Self-publishing may be a good option if you want to own the rights to your book, or if you already have an easily accessible target audience for a very specific topic. Ella Ritchie, founder of Stellar Communications, outlines the pros and cons of choosing the self-publishing route. Ultimately, it’s a personal decision for each writer to make..

Now That You Have a Written Proposal, What Do You Do With It?

There is not an industry standard for how long to wait for a response; it could be days, weeks, or months. Think about how long you are willing to wait, and if you get to that point, move on to another prospect.

Pull out that list of potential agents or publishers, and submit your proposal according to their specific submission guidelines. And then you wait. No response is a rejection, and it happens all the time.

Sometimes the best way to pitch your book is face-to-face with an agent. Easier said than done, right? Writers’ conferences are a perfect way to track down targeted agents, and sell your story.

It’s critical that you seek out specific conferences where appropriate agents are attending. Writer Dana Sitar put together a great list of options in a blog post for The Write Life. Find out who will be there, and plan a targeted approach. The good news is that any agent who attends a conference is actively looking for new authors, so don’t be shy.

“Agents only go to conferences when they are open to pitching.” – Jennie Nash

Many conferences require an additional fee for direct access to agents, and Nash says this is definitely worth the expense. Depending on the conference, these face-to-face meetings with agents could be informal discussion sessions, or they could be literary “speed dating” where you have a couple of minutes to pitch and then move onto the next agent.

Reviews on speed dating are mixed, and most everyone agrees it’s a high-stress situation. If you participate, make sure you have planned your short pitch in advance. “Short” is the key here; be ready to sell your proposal in just a couple of minutes.

Don’t Blow It. Be prepared and you can avoid some common pitfalls.

- Create a well-crafted “mini speech” in advance. This is not the time to ad lib. Be conversational, but direct and make good eye contact.

- Find a conference that represents what you are selling. It makes no sense to attend a romantic novel conference when you are selling a how-to guide for home repair.

- Wait to attend a conference until your proposal is complete, edited and as perfect as you can make it. Sometimes writers approach agents at conferences on somewhat of a whim, just to get an initial reaction. Nash says this is a bad idea and wastes everyone’s time.

Get Started!

Yes, it’s a long road to becoming a published nonfiction writer, but a good proposal is the first step.

Take your time and create a proposal that is as good as the book itself. Know your strengths and weaknesses, and plan accordingly.

If you lack an author platform, then start building an industry presence.

And if, despite being an industry expert your writing skills leave a bit to be desired, find a ghostwriter. Pair your expertise with solid writing, and get ready to be published.