Writing a family history book can be a tremendous gift for your family, especially for future generations.

But it can also be a daunting project. There could be seemingly unlimited amounts of research to dig into. Should you conduct interviews? If yes, then how many should you do?

Just what should you plan on including in your family history book?

First, Determine your Goal for your Family History Book

A family history project can take on many different forms. It could reach far back through many generations, or it could cover a shorter, but significant, period of time.

You may wish to focus on the life of one particular person or provide brief accounts of many.

Pinpointing what you hope to accomplish with your project will help you determine its scope and direction.

If this is your first experience with a family history, you may want to keep the scope of it more limited. You’ll have a better chance of completing the project, and it will help keep you on track.

If your goal is to create a thorough documentation of your family to share with future generations, then you will need to conduct a significant amount of research.

Do you see it as a reference document or more of a narrative account? For the former, you can focus on collecting records of facts. For the latter, you will need supporting materials to add context and stories to round out the presentation of your family’s history.

If you are hoping to create a more visually interesting and engaging type of family history book, here are some suggestions you can explore to help you accomplish this goal.

Bring Your Family History to Life with Personal Anecdotes

Including stories about individuals, and sharing details about their personality and character, is a great way to bring people to life. This is why family history interviews can be so valuable.

You can interview living family members about their own lives or gather stories and memories about relatives who are no longer living,

The more in-depth you can get into an interview, the more rich details you can include in your family history book.

Some family members may prefer to answer questions in writing, and this can be an efficient way to obtain factual information about dates and locations. But in-person interviews are often the best source of stories and memories that come to mind during the back-and-forth of conversation.

These conversations can take many hours, so you will need to gauge how much time and effort you can devote to them. For ideas about what questions to ask, here’s a good resource with a list of suggested questions.

Use Photos and Images for a Richer Experience

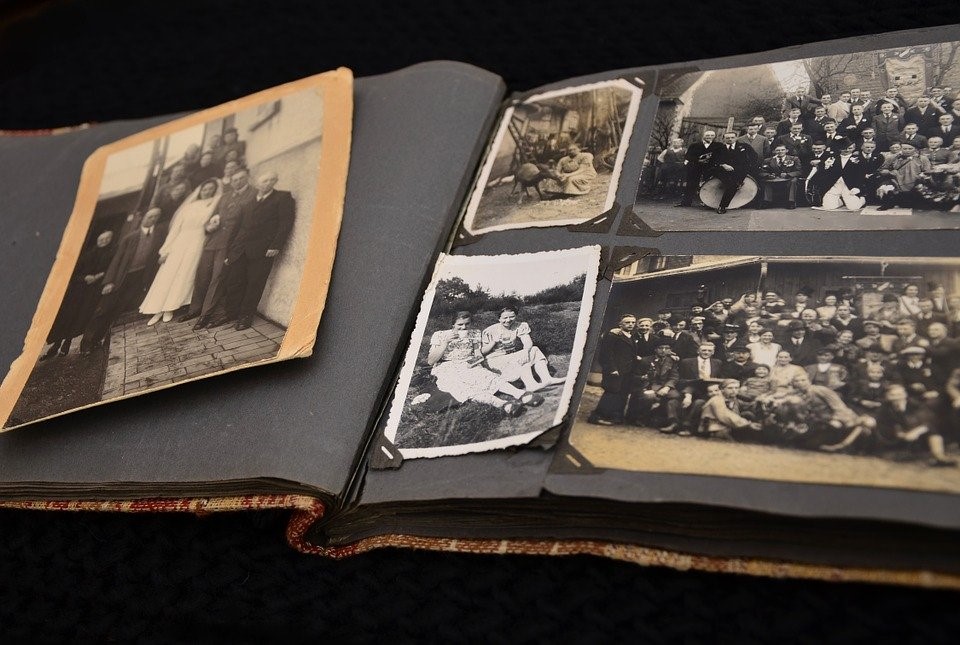

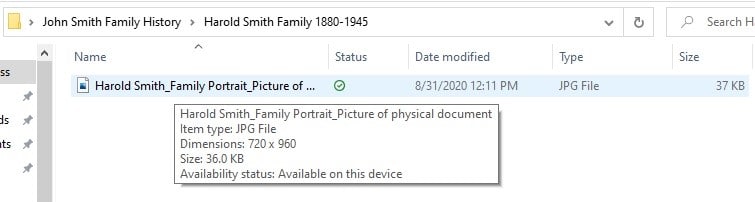

Photos of Family Members

The most obvious photos you should try to include are those of family members whose lives are covered in the family history book. If possible, include photos from different stages of the subjects’ lives. These images can tell an interesting story all on their own.

Today, obtaining photos from far-flung family members is easier than ever. You can simply ask them to scan their photos and email you the digital copies of the images. There are a number of ways to scan and digitize photos. You can do it yourself with a scanner at home or even with a smartphone. Or you can make use of a professional service — which will usually give you the best results.

This article from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) explains the pros and cons of the different options and provides some suggestions for equipment and services that can help.

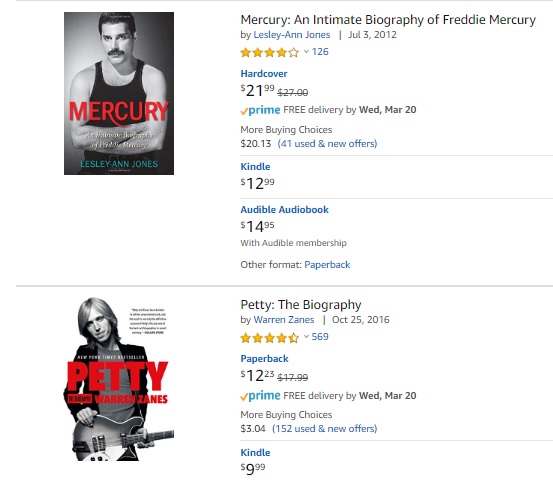

Period Photos

The world has changed drastically over the last several decades. Even if no photos exist of your actual family, or where earlier generations lived, you can still provide context by including relevant period photos.

For example, if earlier generations immigrated from a different country 100 years ago, you could find photos depicting that time period. An image of a typical homestead from an early settler could be used to illustrate what it was probably like for your own family members if they were also homesteaders.

Or, if your family originated in a different country, you could include images of what the town or city looked like during the time period when they lived there.

Even if images are not from the same era, they can still provide context if the landmarks are interesting.

One man we worked with recalled how his father used to ice skate on the lakes surrounding the palace where Korean kings used to reside. While we didn’t have an actual photo of his father ice skating, a present-day photo of the palace and its lakes still provided an interesting and relevant visual to support this memory.

Keep in mind you may need to obtain permission to reproduce any images that are not from your personal collection. It’s best to make sure you can legally use an image before proceeding.

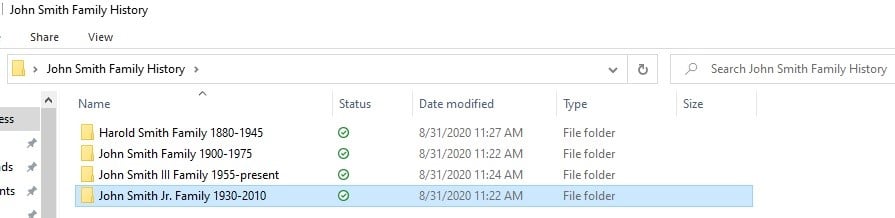

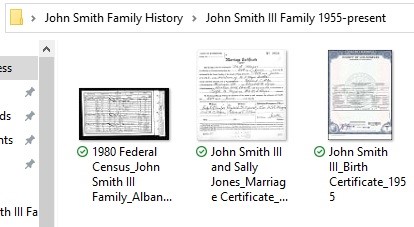

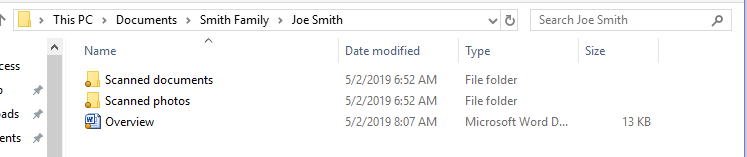

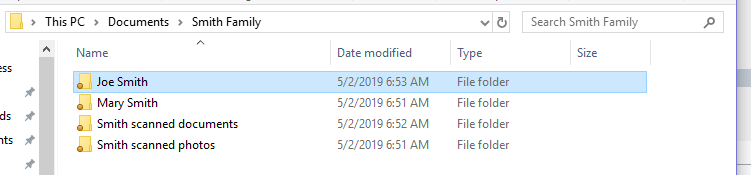

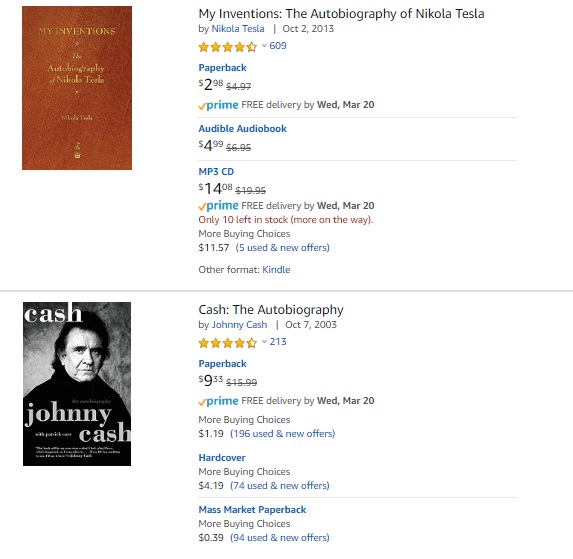

Make Use of Interesting Documents

Official documents, such as birth or marriage records, passports, and even school report cards, can provide something visually interesting to support important milestones or even minor ones.

Copies of personal correspondence, or anything written by hand that has special meaning, such as a family recipe, can help bring individuals to life.

To show the historical context, you can include newspaper clippings of any noteworthy news events from the relevant time period. Maps are also useful for illustrating where people lived and how members of the family moved around.

Another useful graphic that is simple to create is a timeline showing major events in your family’s history. These can easily be created with either word processing or spreadsheet software.

Liven Up the Narrative with Dialogue

Interspersing your family history with the actual words either written or spoken by family members adds another interesting dimension. The way people speak and write often conveys their personality and can bring them to life on the page.

If you conduct interviews of family members, try to include some exact quotes that add color and convey personality. Not only does this make for more interesting writing, but it also gives readers a glimpse of what the interviewee was actually like.

Pulling excerpts from letters is another way to include exact quotes. If you are fortunate enough to have copies of correspondence, this is a wonderful way to make use of these gems. You can take photos of them and highlight relevant passages as a way to provide both the actual words of a family member and an interesting visual.

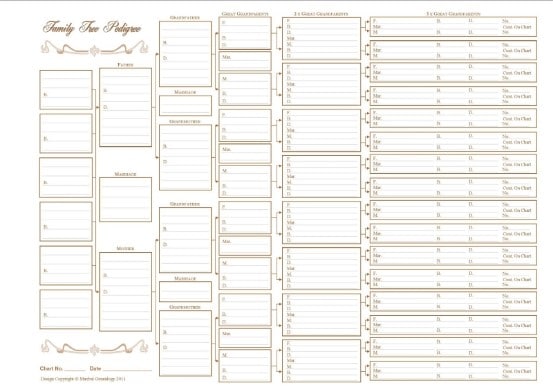

Create A Visual Family Tree

https://freefamilytreetemplates.com/blank-family-tree/

Showing your family’s lineage can be complicated and even boring if you rely on lists or straightforward charts.

There are many creative ways to illustrate your family tree. Some people like to include photos to represent different family members. Others make use of graphics to make charts more visually interesting.

Much of this decision will depend on how large and how complicated your family tree is. You will need to keep space limitations in mind if you hope to include several branches of your family. Or you can display different parts of your family with their own separate visual graphic.

There are many free templates available to help you design your family tree graphics. Family Tree Magazine has a number of templates that are free to download from their website. There are even simple templates that can be used with Microsoft Word.

Consider Including a Reference Page

When writing a nonfiction book, writers inevitably end up with reams of interesting research that doesn’t make it into the final story. This can be because of space constraints or because they take away from the readability of the book.

When you are creating a family history, you are usually not trying to win the National Book Award. Much of the research you have compiled may actually be worth preserving.

But if you are trying to write a family history narrative that is also readable, cramming every bit of research into the book may not be feasible.

One way you can have both an interesting family history book and share bits of research that don’t make it into the book is to include a reference section. This can include citations for your research so the information can be tracked down, if necessary. It can also contain a section of back matter, which is where you can provide more details or facts about your family history.

Don’t Underestimate the Work Involved

Writing a family history is a wonderful gift to create for your family and will be appreciated for generations to come. But it is a major undertaking, requiring hours of research, organization, and writing.

Keep in mind there are many resources available to help you complete your family history project. With so many different ways to approach the project, you are sure to find one that matches your vision.