One of the most challenging aspects of technical writing is communicating effectively with a subject matter expert (or SME, commonly pronounced as one word “smee”).

SMEs have the knowledge that the technical writer must extract and translate into useful publications, such as documents, videos, webinars, classroom courses, and marketing collateral.

In some cases, the technical writer conducts interviews with a SME to gather the appropriate information. In many other cases, the technical writer proofreads, edits and restructures documents that a SME has authored.

This process is similar to a writer who converts the rough draft of a celebrity’s autobiography into a publishable book. In this regard, we can think of a technical writer as a technical ghostwriter.

To succeed in this process, the technical writer must be able to understand and assimilate what is often highly complex subject matter.

However, a more important prerequisite for success might be the ability to manage interpersonal communications.

According to Sandra Williams, a long-time senior technical writer and instructional designer with Hewlett-Packard Inc., “effective communications with SMEs is more about managing the relationships than about procuring the material.”

So for the purpose of eliciting information from SMEs, technical ghostwriting may be considered more of an art than a science.

The following are methods that some of my colleagues and I have found useful in our many years of practicing the art of technical ghostwriting.

Managing Communications with SMEs

You may be wondering how a technical ghostwriter can improve your chances of obtaining highly effective marketing and training deliverables from your SMEs. Here are a few tips and tricks, my colleagues and I have found useful:

- Timing is everything. I once worked with a SME who was very busy throughout the day until about 4 P.M. By then the SME was so tired, he would need a Mountain Dew (his favorite soft drink) for refreshment. So, I would schedule our meetings for 4 P.M., and I would bring two cans of Mountain Dew along. It might sound a little corny, but we had much more effective information exchanges thereafter, than we had before I knew the SME’s routine and preferences.

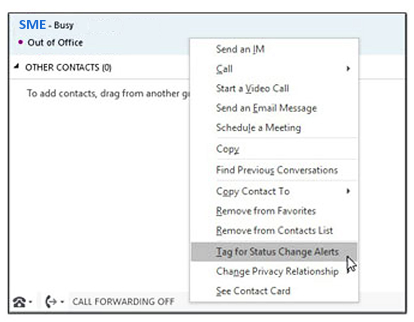

- There is no ‘one size fits all’ when it comes to SME communication. The writer should determine the SME’s preferred form of communication and use it as the first option when contacting the SME. Some people respond more readily to e-mails, some to text messages, some to phone calls, and some to in-person visits. Of course, at times SMEs will be unresponsive, especially when they are busy or under deadline pressure. Many technical writers have experienced a SME avoiding them, so writers should be persistent and resourceful. Sandy Rogers, a Principal Technical Writer with Hewlett-Packard Inc., likes to tag a SME on Skype so she is most likely to make contact at a mutually convenient time.

- SMEs are more likely to help the writer, if they like the writer. It’s human nature. An effective writer uses people skills to foster personal relationships, so that SMEs are more likely to prioritize their mutual projects. Sandy Rogers puts it like this: “I like to personalize my interactions with SMEs. They are people too, and they have interesting lives, both in and out of work. I usually begin an interview by asking how they’re doing in general, and also how they think the project is going. This provides an opportunity for them to vent any frustrations they may have, or to take a moment and reflect on a personal story. I find that this approach tends to improve rapport and makes it easier to elicit the project information that I need.” Sandra Williams agrees: “No matter how much I need a review done, I try not to open a conversation by asking if anyone has looked at the material yet. I always ask how everyone is doing first.”

- A little bragging goes a long way. Many SMEs have had poor relationships with unqualified writers in the past. Especially when working on a new project, a writer should consider providing the SMEs with a summary of their qualifications and competencies. For example, Sandy Rogers started her career as a Call Center technician. She has detailed technical knowledge to the circuit board level, as well as first-hand knowledge of typical customer service issues. Sandy finds that this experience sets a comfort level with fellow technical professionals. She is able to speak the SMEs’ language in addition to translating their specifications into effective documentation.

- There is no substitute for proper preparation. The writer should be fully prepared before a meeting with a SME. The writer should know exactly what to obtain from that meeting. The preparation should include a meeting agenda and objectives. The writer should mark up any manuscript drafts to notate those areas that require further discussion.

- SMEs have feelings too. Good technical writers must have tact in their tool bags. With diverse multicultural work forces, English is very often not a SME’s primary language. It might not be their secondary language either. In these cases, avoid being overly critical of the SME’s grammar or wording. The writer can function as a coach and as a mentor to help those SMEs become more conversant in English. It will be appreciated, it will make the writer’s job easier, and it will result in more effective content.

- Focus on mutual goals. Another important attribute for an effective ghostwriter is to be positive and encouraging. Even those of us for whom English is our primary language know how discouraging it can be to work long and hard on an assignment without any positive feedback. A positive attitude encourages the SME to persist in what can be a lengthy and sometimes tedious writing process. A good writer constantly reminds a SME that the finished product is more of a credit to the SME than to the writer.

- Templates are tools, not substitutes for SME-writer communication. Many of our clients use standardized templates to encourage SMEs to provide all of the required information, especially for technical specifications. A template works well to focus a SME on furnishing all of the significant details. It can also relieve the writer of some of the restructuring and reformatting that might be necessary in the absence of any such turnkey solution. Very often, however, due to time constraints and deadline pressure, a SME will not prioritize the writing function. In these cases, rather than adding more pressure for a SME, Sandra Williams might offer to complete the template herself. “I’ll schedule a convenient time for us to sit down for an interview, and I’ll use the template as a guide to get the right information. This saves time in the document conversion process too, as I’ve already asked many of the questions that I would have had if I was reading a spec the SME wrote.”

- Consider mini reviews. While it is a constant temptation for writers to try to secure lengthy blocks of uninterrupted writing time, it can be more efficient for some SMEs to write and review smaller pieces of content at a time. Otherwise, reviewers can get bogged down or discouraged reviewing longer tracts. Moreover, it is often difficult for reviewers to set aside a solid block of review time, so “chunking” the content into smaller review cycles can encourage more effective feedback.

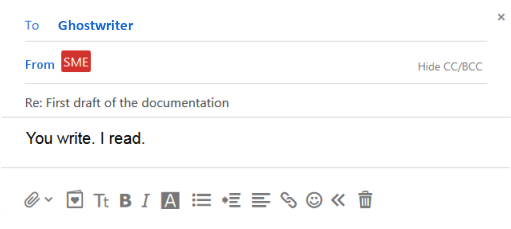

- It’s all about the SME. Rather than trying to push all SMEs into providing large amounts of information upfront, a considerate writer will take each SME’s personal circumstances into consideration. For example, years ago I wrote a detailed, somewhat verbose message to introduce myself to a far-flung SME whom I had never met.

I received the following verbatim response from the SME:

That was the very succinct response, and that’s what we did. I wrote and the SME read.

Over time, we were able to overcome the geographic, linguistic and cultural differences between us to create a useful set of documents that contributed to the successful release of the product.

The role of the technical writer

At the end of the day, the technical ghostwriter is an advocate for your customers and end users.

Technical SMEs are highly skilled professionals who are motivated to develop the best possible products, but that is their priority: product development.

Without the role of the technical writer, the end user experience can easily get lost in the development process.

The celebrity ghostwriter translates a subject’s life experiences into an enjoyable story.

The technical ghostwriter translates complex technical content into cogent and effective instructions that make technical products easier to learn and easier to use, while enhancing the user’s ability to integrate those products into their own work and life experiences.

In sum, the technical ghostwriter is telling the story of the fabulous products the SMEs are developing.

Technical ghostwriting is the art of procuring SME source material, in its myriad forms, and transforming it into highly readable and effective documentation, marketing collateral, and training guides.

That’s it in a nutshell. That’s what we do.