So you’ve just written your first draft. Congratulations! Getting words onto the page can be one of the most painful parts of the writing process.

Unfortunately, you’re not done yet.

As every seasoned writer knows, your first draft is just the first step. Rarely (if ever) does a piece move from the writer’s brain to the page in a single flawless leap.

So how does a writer go about editing their own work?

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide that will help you turn your so-so copy into powerful prose.

The Elements of Editing

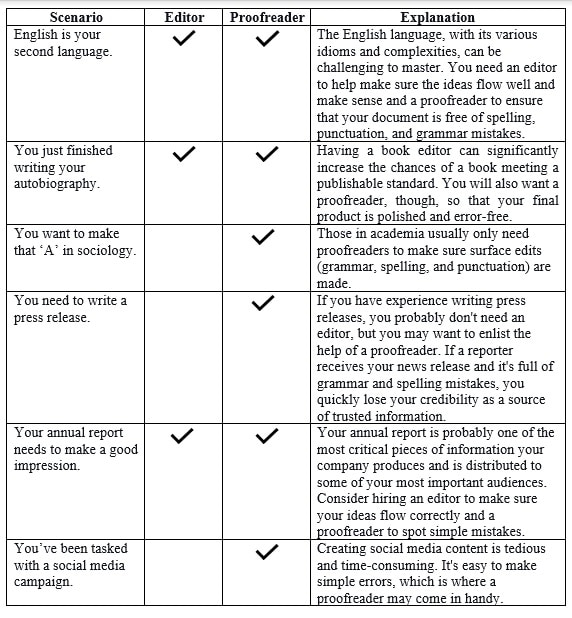

When we use the term “editing,” we’re referring to the high-level reading and revising all writers must undertake to ensure their ideas are communicated clearly, succinctly, and with maximum impact.

In publishing terms, editing in this sense is a combination of developmental editing and copyediting.

When you edit your own work, you’re looking for big-picture changes—rearranging paragraphs, rewriting sentences, adding or deleting information—that will help reshape the content into a better version of itself.

This includes casting a critical eye toward the following:

- Structure: Is the piece organized in a logical way that allows readers to easily follow the thread of your ideas?

- Content: Have you provided the reader with all the information they need to understand the intended message? Have you defined unfamiliar terms and concepts, provided background when necessary, deleted extraneous information, and checked for redundancy?

- Consistency: Are the facts and details you provided consistent throughout the document? Have you unwittingly introduced any contradictory information?

- Sentence construction: Are your sentences worded clearly and without clumsiness? Are there places where readers misinterpret your meaning? Do your sentences vary in length and use the active voice?

The Elements of Proofreading

In contrast to the deep dive of developmental editing and copyediting, proofreading is a more straightforward undertaking that involves looking for surface-level errors.

In a publishing house, proofreaders are typically the last set of eyes to look over a text before it goes into production.

Their job is to catch all the little things that developmental editors and copyeditors may have overlooked while evaluating for big-picture changes.

Proofreading involves reviewing for the following:

- Spelling and grammatical errors, such as misspelled words, subject-verb disagreement, misplaced modifiers, etc.

- Correct use of punctuation, including periods, colons, dashes, and apostrophes

- Formatting and typesetting mistakes, such as consistent use of bolding, italics, and bullets

- Stylistic inconsistencies, particularly as they pertain to the chosen style guide (Chicago Manual of Style, Associated Press Stylebook, etc.)

A Step-by-Step Guide to Editing Your Own Writing

Now that you’re familiar with the two levels of editing, let’s talk about how to go about it.

All writers have their own way of approaching the editing process. The longer you write, the more likely you are to land on a method that works best for you.

Until then, below is a step-by-step guide to help you get from first draft to final draft as painlessly as possible.

1. Take a Break

Editing your own writing requires fresh eyes.

Never try to start editing immediately after completing your first draft. At minimum, give yourself 24 hours between completing a draft and starting the editing process to give your brain time to rest and reset.

Even better, wait several days before diving in.

2. Know Your Audience

What type of person do you intend to reach through your writing? Is your work designed to entertain or to educate?

Are you an expert explaining a topic for the layperson, or are you writing for other professionals in your field?

Keeping your audience in mind throughout the editing process will help you assess the structure and flow of your piece, as well as ascertain whether certain information is necessary or superfluous.

The tone of your writing—casual, formal, or somewhere in between—should also be decided based on your intended audience.

3. Plan for Multiple Rounds of Editing

Trying to find all the mistakes in your writing in a single sitting is a recipe for disaster—not to mention exhaustion.

Instead, plan to do multiple rounds of editing. Each one should focus on a specific purpose.

How many rounds are necessary? This will vary depending on the length and complexity of your writing, as well as external factors like deadlines.

Nevertheless, try to plan for at least three rounds.

The first round of editing should focus on big-picture elements, like the structure, tone, and flow of the piece as a whole.

Next, read your writing sentence-by-sentence, editing for elements like syntax, word choice, clarity, and redundancy.

For the third and final round of editing, proofread your almost-final draft to catch any surface-level errors like misspellings or formatting mistakes.

4. Zoom Out for a Big-Picture Edit

On your first round of editing, avoid reading too carefully. Instead, do a “big picture” edit to assess the structure and flow of your piece.

This is the time to decide if paragraphs need to be moved around or deleted, if additional context or background information is needed, or if certain information is superfluous or redundant.

Ask yourself: Is the writing arranged in a way that’s both clear and compelling? Would certain sections benefit from being divided up or rearranged?

Is any information missing? Is all the included information serving a purpose?

Take notes as you read, then make revisions as needed.

5. Zoom In for a Closer Look

After you’ve done your big-picture edit, it’s time for a deep dive. On this second round of editing, you will examine your writing sentence-by-sentence.

Here are some common mistakes to look out for:

Check for passive voice: Passive voice construction means that the subject is the receiver of the action. Rewriting these sentences in the active voice—i.e., making the subject the performer of the action—will almost always result in a stronger, more direct statement.

- NO: Our services are offered by dedicated professionals.

- YES: Dedicated professionals are on-hand to deliver our services.

Avoid generalities: Good writing is in the specifics. Whenever you spot a generality, try to replace it with specific information.

- NO: Our products save you time.

- YES: Using this patented system, customers report saving almost two hours a day.

Crush your clichés: Clichés are a waste of space, plain and simple. Whenever you spot one, replace it with a specific example or delete it altogether.

- NO: At our company, we think outside the box.

- YES: The Better Business Bureau ranked our company among the best for small business innovation.

Use positive language: Rewrite negative statements using words like “can’t,” “never,” “not,” “hardly,” “barely,” and “none” so that they use positive language instead.

- NO: We would not be successful without our dedicated customers.

- YES: Our dedicated customers have made our success possible.

Keep it simple: Don’t go out of your way to use obscure words and phrases when more common choices will suffice. While the thesaurus is your friend, you don’t want to alienate your readers by using words they’re unlikely to understand.

- NO: We offer a variety of delectable accoutrements to complement our small-batch ice cream.

- YES: We offer an assortment of delicious toppings for our small-batch ice cream.

Use modifiers sparingly: Adverbs and adjectives can often be eliminated by opting instead for vivid verbs and strong nouns.

- NO: This difficult problem was in need of a solution.

- YES: This challenge was in need of a solution.

- NO: He looked intensely at the flyer.

- YES: He scrutinized the flyer.

There are also certain overused and/or superfluous phrases to be on the lookout for. In most cases, sentences containing the phrases below can be rephrased to be more concrete and concise:

- That’s why…

- Our goal is to…

- Our mission is to…

- We believe…

- Our vision is..

- We pride ourselves on…

- The fact that….

- In order to…

- There is…/There are…

- It is necessary/important/crucial that…

Here are a few examples of the above sentences that can be re-phrased:

- NO: Our mission is to cut costs.

- YES: We cut your costs.

- NO: Our team lost revenues owing to the fact that we were understaffed.

- YES: Our team lost revenues because we were understaffed.

- NO: There are roses on the patio.

- YES: Roses grow on the patio.

One final tip: In his book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, Stephen King declared that a writer should aim to reduce the word count of their first draft by at least 10 percent during the editing process.

While 10 percent is not a hard and fast rule, don’t be afraid to be ruthless.

Here are a few things to look out for when it comes time to slash and burn:

– Redundancies: If your ideas are communicated clearly, you only need to explain them once. Scour your text for places where you may have restated the same idea or concept multiple times. Choose the best one and delete the rest.

– Digressions: Every piece of information included in your work should serve a purpose. Check your writing for areas where you may have descended into tangents or included information that’s unnecessary or irrelevant.

– Needless transitions: Words like “indeed,” “however,” “nevertheless,” “likewise,” and “similarly” are often unnecessary and can interrupt the flow of your writing. Reading your work aloud can help guide you on when these transition words should be deleted.

4. The Final Step: Proofreading

Proofreading, like more high-level editing, is a skill that isn’t easily cultivated.

Just as with solving math equations or learning a foreign language, some people simply have a knack for noticing small errors that other eyes easily gloss over.

Nonetheless, there are certain best practices you can follow that will make you more likely to catch glaring, potentially embarrassing errors in your own writing.

For our list of proofreading tips, visit A Proofreader’s Checklist.